Fatty Taylor

During a recent interview with Larry Jones, one of the great but sadly unsung guards of the old American Basketball Association (ABA), the name of Roland “Fatty” Taylor came up. “Here’s what I tell people about Fatty,” said Jones, his low voice rising to make a point. “He wasn’t much of a shooter or leaper. But, man, I used to hate to see him coming.” Jones explained that Taylor was among the ABA’s most asphyxiating backcourt defenders, a six-foot stopper who showed up every night, baseline to baseline. As Taylor today laughs, that’s just how he learned to play the game back in the early 1960s on the playgrounds of Northeast Washington, D. C. “You had to be tough and relentless,” said Taylor of his asphalt apprenticeships at Watts Branch and later high-profile Kelly Miller playgrounds. “You always took the challenge; there was no backing down.”

Taylor, now 66, continues to take the challenge in his adopted home of Aurora, Colorado. He runs the non-profit Taylor Made Playaz, an independent basketball and mentoring program. Despite the Rocky Mountains now replacing the Washington Monument as his point of reference, Taylor remains true to his D. C. roots and still thanks those who helped “a poor kid from the projects” beat the longest of odds to attend college (LaSalle University), play eight years of pro ball, and today lead a comfortable life. Recently, Taylor told his story to D. C. Basketball, starting with the genesis of pro legend George Gervin’s nickname as “The Iceman.” According to NBA.com, Taylor dreamed up the moniker one day based on Iceberg Slim, the literary character/pimp of 1960s fame. Not so, sez Fatty, it all happened like this . . .

. . . George Gervin and I played together with the Virginia Squires back in 1973. That was the year that Virginia traded Doc [Julius Erving] to the New York Nets, and the Squires were heading up there to face him for the first time since the big swap. On the flight to the game, I sat next to George. I can still remember he had the inside seat, and I sat in the aisle seat. Well, George absolutely idolized the Doctor. He was sitting there next to me reading an article about the great Doctor J, and I glanced over and said, “Hey man, you can always respect a guy. But never praise him. You still got to play against him.” I said, “Tell you the truth, George, you’re every bit as good as he is. Matter of fact, I think you’re better!” That was about the most blasphemous thing that he’d ever heard in his life, and George immediately started crawling over the seat to get away from me. So I told him, “Listen here, you’ve got a better shot, you handle the ball better, and you pass better than Doc. The difference is the Doctor just goes harder than you. You play easy.”

And it was true. I used to watch George and the Doctor play one on one after practice before the trade. They’d try to outscore each other. The only difference was when George made a move to the hoop, he’d use a finger roll and lay the ball up softly; when the Doctor went to the hoop, he dunk the ball and try to bring you into the basket with it.

To be honest, I was trying to pump up George and get him to go harder in New York. When the game started, George and the Doctor guarded each other. The Doctor swooped to the hoop for a bucket, we trotted back down on offense, and I threw the ball to George. He tossed it back to me. I said, “Oh no,” and I threw the ball right back to him. So, the two went after each other the whole game, and we ended up beating the Nets. I think George finished with 40 points that night. In the locker room, I noticed that George didn’t have a lick of sweat on him. I said, “Hey man, you scored 40 points, and your uniform isn’t even wet. I don’t see any bruises on you, and you don’t look like you’re tired. You don’t even look like you just played a basketball game.” He started laughing, and I said, “Man, you’re too smooth. I’m going to start calling you the Iceman.”

The reporters started filtering into the locker room, and they were asking for George. They said nobody was supposed to outshine the Doc in New York. One said, “We’ll have to start calling you Doctor G.” George was still a little shy and didn’t quite know how to handle the press. He mumbled back, “No, just call me the Iceman.” The name stuck. Iceman, Iceman, Iceman! When we get together now, he jokes, “Fatty, you made a mistake. You should have put a patent on my name.”

A Fat Baby, The Projects, and Kelly Miller

Enough about the Iceman. How did you become Fatty?

My godmother gave me the name. I was a fat baby, and the name has stuck.

Where’d you grow up in Northeast D. C.?

The East Capitol Projects. They were just across the line from Fairmont Heights, Maryland. My family moved there from Foggy Bottom when I was only about 10 or 11 years old. You know how it goes when a kid moves into the projects?

You had to fight?

Yeah, I had to prove myself to the other kids. I’d get up in the morning, go outside, and somebody would pick a fight with me. Boom. I’d beat the kid up. The next day, I’d get up, go outside, and another guy wanted to have a shot at me. It wasn’t whether I was going to fight; the question was, “Who am I going to have to fight today?” So, I made it to 7-0. I’m feeling good now and, for my eighth fight, I went against a little guy named Tadpole, who was a couple years older than me. Tadpole beat me bad. I’m throwing roundhouse punches, and he was straight jabbing me. That’s when I learned to never underestimate anyone, even Tadpole, who today remains a close friend.

When the fists weren’t flying, you played a lot of baseball?

Oh, I was a heck of a third baseman. When I stepped on the diamond, I knew I was the baddest thing out there.

But you quit baseball. Why?

Recognition. I was maybe 12 years old, and my baseball team had played in the city championship game. I think I hit two home runs that game and made a few nice plays in the field. But afterwards, I walked across the park and heard a throng of people hollering at the basketball court. There was a tournament going on. I remember thinking, “Here I had played in a championship game, swatted two home runs, and ain’t nobody watching me. I think I’ll start playing basketball.”

Was it a steep learning curve?

Oh, yeah. Everybody said, “Stick to baseball. That’s your game.” But I’d made up my mind. I started working out at 7 a.m. every morning at Watts Branch Playground before anybody arrived. I’d dribble for 15 minutes, work on my footwork, that kind of thing. It was all full court. If I wanted to make a lay up, I’d run down to the other end. If I shot a jump shot, I’d get the rebound and go the other way.

You were determined to become a player?

Right, right. I was determined to make it. I started getting into the games at Watts Branch. But Kelly Miller Playground was our Mecca back in the late 1950s and early 1960s. That’s where all the brothers went to measure their games. If you held your own down there, you were considered one of the best. If you came down there and froze up, then the guys would say, “Shoot, he ain’t no good.” Now, if you went down there and didn’t show well, you could always come back. It wasn’t like you were judged on one performance.

What was the style of play?

A lot of one on one, but it was team oriented, too. You didn’t have any guys come down and shoot the ball all of the time. We’d jump on anybody for doing that.

So, everybody knew to pass and cut?

That’s right, but it wasn’t any slow-down stuff either. You’d grab the rebound, get the ball out, and go. Back then, you didn’t say you were a point guard or a two guard. You were a guard, and you played.

When did you start playing at Kelly Miller?

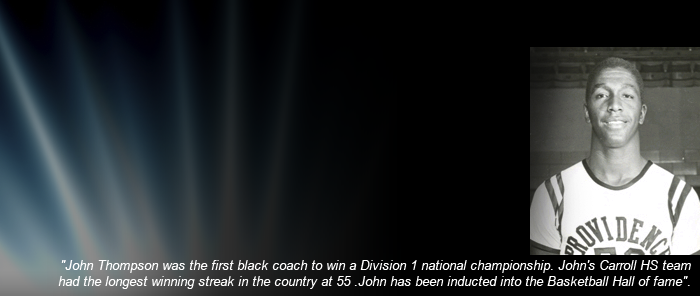

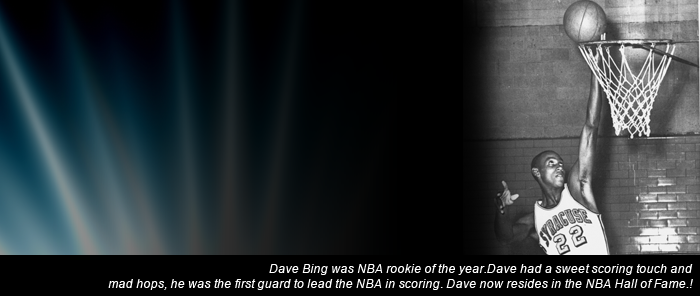

I was 14 or 15 years old. At first, I stood behind the fence and watched. Back then, guys from New York would come down to play the D. C. guys – Jackie Jackson, Connie Hawkins, those types of players. Oh man, it was something else. I watched John Thompson, Willie Jones, Dave Bing, Bernard Levi, Roy Wilkes, Sleepy Harris, Artie Johnson, Tom Hoover. All the bad guys. There were some games, man.

And then you started getting in the games?

Yeah, it was like playing against the pros. You had to get there early, say at 7 o’clock in the morning. If you lost, you might not get another game for three or four hours. We’d play 30-point games and count by two. Now, if the score was tight, say 28-28, you didn’t allow any layups to win the game. If the other team started on a fastbreak and you were close to the ballhandler, you tackled him or whatever it took to make sure they didn’t get a layup. If you didn’t tackle him and lost the game, your teammates would be ready to jump on you. You just didn’t want to sit around all day long waiting for the next game. It was serious business.

What did you take away from these games?

Toughness. You had to be tough and relentless. You could never back down. You took the challenge. Now, you played honest, too. You didn’t go out trying to hurt anybody. But you had to be physical and not be intimidated.

Skeeter, Spingarn, and a Trip to the Barber Shop

One of the turning points in your life was Skeeter Douglas. Tell me about him?

Oh, what a great man. When I was in sixth or seventh grade, Milton “Skeeter” Douglas was the recreation director at Watts Branch Playground. He’d just graduated from college. Mr. Douglas had a little Volkswagen that he’d drive up to the playground. Everybody would run up to his car to greet him. He was the man.

And a visionary?

Absolutely. He got people in the projects to start thinking that they could chase their dreams – and succeed. What this one man alone did for our community was awesome, man. He made us believe.

Let me tell you a quick story. In the projects, we used to hang out. That’s just the way it was. One day, Mr. Douglas drove me uptown to his home turf. He got out of the car and started talking with some of his old buddies. They were drinking wine, and a couple of girls were hanging with them, I remember one of the guys wore his high school letterman’s jacket, even though he’d been out of high school for several years. Mr. Douglas got back in the car and said, “You know why I took you here? All of those guys were there before I went to college, and they’re still there.” He said, “So, don’t think you’ll be missing anything when you go to college. They ain’t going nowhere.”

But you almost never got to college.

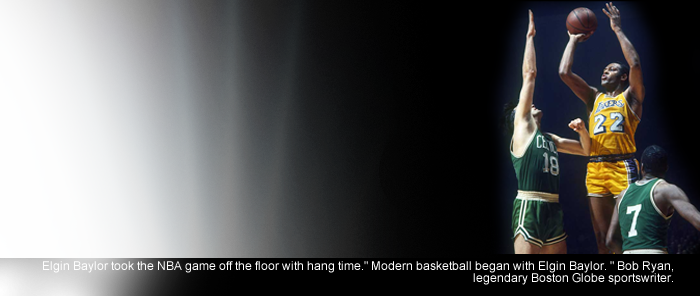

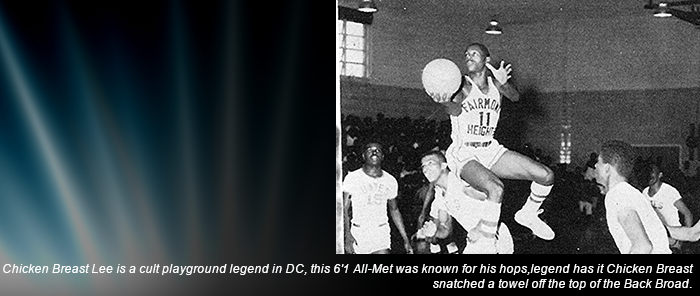

That’s true. I attended Spingarn High School in the District. The competition was so tough to make the team, everybody sat out a year and then worked their way into the rotation to play four years. Dave Bing repeated a year, John Tresvant repeated a year, Elgin Baylor repeated a year, and so did I. In my senior year, they changed the rule, and that meant I was ineligible in the District. But in Maryland, the old rule was still in effect. So, I transferred with two other Spingarn guys to Fairmont Heights High School.

I heard FairmontHeights had a real powerhouse.

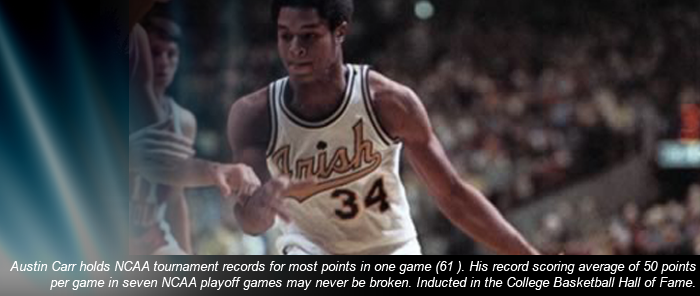

And that was the problem. Fairmont Heights had won the state championship the year before with a group of seniors, and our team was even better. People wondered how that was possible. A formal investigation ensued and, for whatever reason – and it wasn’t fair - they kicked us off of the team. Funny thing was Harold Fox [a fantastic guard who would play with Artis Gilmore at Jacksonville University] stepped in for me. Harold was a freshman, and he scored 40 points in his first varsity game.

Did you get any college offers?

No, I fell off everyone’s radar screen because I didn’t play my senior year. But I kept pushing. I was a strong-willed kid and absolutely determined to make it.

And that’s when you decided to go West?

Yeah, it’s a funny story. It was the dog days of August 1965, and I was sitting in a little barbershop on Dix Street, N. E. The place was crowded that day, so I picked up a magazine to kill time. I saw an advertisement for a junior college in Dodge City, Kansas. I said, “That’s where I want to go.”

Why?

That year, a U. S. Marshall shot and killed one of my friends. Then another buddy died. So, I had to get out of D. C. I also knew that I had to get as far away as possible from the projects, and Dodge City sounded like it fit the bill. I went home and wrote the coach. I told him that I was six foot three and was interested in a “look-and-see” scholarship. That’s when you pay your way to try out for the team, and the coach either keeps or sends you back home. I addressed the envelope, “Basketball Coach, Dodge City Junior College, Dodge City, Kansas.” The coach wrote back and said okay.

A Greyhound Bus, Tumbleweeds, and Redemption

And you said, “Dodge City, here I come.”

I went down to the Greyhound bus station and bought a ticket. My mother had packed me a lunch, and I remember her telling me, “Fatty, I don’t have any money to give you. But you go out there and put your best foot forward.” To be honest, I was so naïve that I didn’t even know which direction Kansas was. After a few hours, the bus stopped at some doohickey town, and I asked the white, redneck driver, “How much longer until Dodge City, Kansas?” He said, “Boy, before you get there, you’ll change three or four bus drivers.”

Now, I’m nervous as hell. The bus kept pulling into these doohickey towns, and I had no idea where in the world I was. Three days later, the bus finally crawled into Dodge City at four o’clock in the morning. The town was pitch black, the wind was howling, and tumbleweeds were blowing all over the place. It was like I’d stepped onto the set of a Western movie.

Did you have to sleep in the bus station?

No. Dick Brown, the coach at the college, was waiting for me. He walked over and mumbled, “You don’t look six foot three to me.” I said, “No, but I play big.” I got into Coach Brown’s car, and he turned down a back alley and stopped behind this large Presbyterian Church. At this point, I’m scared and thinking he’s up to something. Coach Brown and I walked down a couple of steps to the basement. He opened the basement door, and I saw this big room with a king-sized bed. Coach Brown said, “Roland, I’ll come back at 8:30 in the morning and take you up to the gym.”

No sooner had I laid my head on the pillow than I heard a knock at the door. Coach Brown said, “Roland, it’s 8:30. Let’s go.” I’m thinking I’d been on the bus for three days, and now I have to go audition for the team. If I didn’t play well, our agreement was he’d hand me a ticket and put me on the next bus home!

This is where the D. C. toughness comes in. I said to myself, “Wait a minute, Fatty. You done played against the baddest guys in Washington, D. C. – Dave Bing, John Austin, Willie Jones, Bernie Williams – and you done held your own. Go out there and show them what you can do.”

So what happened?

I played like a man possessed. Afterwards, Coach Brown took me out to lunch and said, “We’re going to work out again tomorrow.” The next day, I duplicated my performance. Coach Brown said, “Okay, Roland, you’ve made the team. I’ll give you tuition and books, but you’ve got to find your own room and board.”

You’re kidding?

No. See, the school didn’t have dormitories. That meant I had to find a job to pay for my food, rent, and so on. I told him, “I didn’t come all this way to get no job. When you get my transcripts, you’ll see that I need to concentrate on studying.” It was true. I didn’t have any study habits. I told him, “You may as well give me that bus ticket right now, and I’ll go on home and get a job. Just drop me off at the bus station.”

I’m bluffing now. I didn’t want to get back on that bus. Coach Brown just looked at me and said, “Okay, we’ll talk tomorrow.” The next day, he told me that I could live in the basement of the Presbyterian Church.

How did things go in Dodge City?

The basketball went great. I averaged 24 points per game as a sophomore and made junior college All American. But Dodge City was real culture shock at first. This was actually the first time that I’d ever been around white people. So, I told myself, “You’re not going to fail.” You know how you hear all of the negative stereotypes about black people not being able to cut it in school. I vowed not to let them think that I fit that mold. So, the first day of class, I’m the only black in the classroom. The professor is lecturing, and the students are jotting down notes. I had no idea what to write down. I’d never taken a note in my life. So, right after class, I walked up to students who looked like they knew what they were doing and asked if I could borrow their notes. I’d read through them and hand them back at lunchtime. I’d do that after all of my classes.

The point being, you weren’t cheating; you were learning how to listen to the professor and take notes.

Right. I would copy their notes and notice how they highlighted certain things. The next class, I’d ask somebody else for their notes. To make a long story short, after a good little while, I figured out how to take notes. And that helped me think like a student. After the first semester, I’d learned something about myself. If I had adequate notes and studied, I could pass any test. I finished the semester with close to a B average. I would get out of class and run home to the church to study. I’d study all day. I kept repeating to myself, “You can’t go back to the projects. If there’s a way out, this is the way to get out.”

But you gutted it out?

Oh, I was determined not to fail. See, back home, they were taking bets on how long I’d last in Kansas. They said I was too short, I’d fail academically, I was a troublemaker, I’d get into a fight. You name it. They were just crabs in a bushel pulling you down. I wasn’t going to let them drag me down. So, I buckled down, and those two years changed my whole life.

When I was ready to graduate from Dodge City Junior College, I had letters from colleges all over the country to come play basketball. I was down in my room in the basement and, all of a sudden, I just started screaming and throwing the letters up in the air. The church pastor, Reverend Burch and his family lived upstairs. When they heard the screaming, the Reverend came racing down the steps and started pounding on my door, “Roland, Roland, what’s going on down there?” I opened the door and asked him to come inside. With tears in my eyes, I said, “Reverend Burch, remember when I came here? Not a school in the country wanted me.” All of the letters were scattered across my bed and on the floor. I said, “Look at me now. I’ve got a B average, I’m All American, and I can go anywhere in the country. Reverend Burch, I’m just rejoicing.” He looked at me and said, “I hear you, brother.”

Bernie, A Tough Coach, and Vindication

From all of those letters, you ended up at LaSalle. How’d that happen?

When LaSalle recruited me, the coach mentioned, “We’ve got one of your homeboys.” I said, “Oh, who’s that?” He opened up a program, and there was the picture of Bernie Williams. I said, “Coach, where do I sign?”

|

What was so special about Bernie Williams?

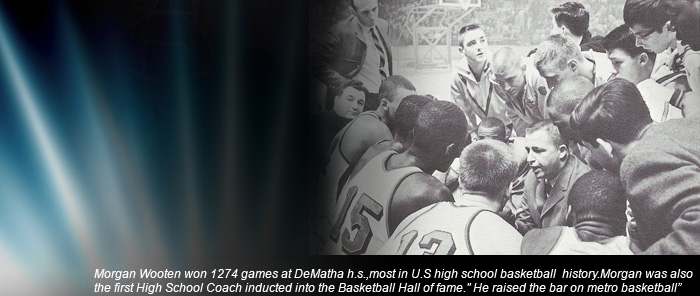

I get chills, man, talking about him. When I was in high school, I went to see DeMatha play New York’s Power Memorial, the number one team in the country with Lew Alcindor. When I left the game, I wasn’t thinking about Lew Alcindor. My mind was on Bernie Williams. Oh, what a beautiful ballplayer he was. He could shoot it, he could jump, he was fast, and, on top of that, he was a nice guy. I remember thinking back in high school, “I sure would like to play with that guy some day.”

And now you got your chance.

Yeah, we ended up being the best backcourt combination in America during our senior year. But things were a little rough during my junior year.

That’s right, you played for the notoriously ill-tempered Jim Harding that year.

He was one crazy guy. Forty years later, if I saw him today sitting in a wheelchair, I’d walk over and smack him. Here’s the deal: It’s the autumn 1967, and Harding has just arrived at LaSalle to turn a good team into a great one. He inherited some fantastic scorers in Bernie Williams, Larry Cannon, and Kenny Durrett. LaSalle just lacked a guard who could run the offense, and that’s where I entered the picture. The problem was Harding had no tact or respect for anybody. LaSalle was a Jesuit school. Priests would wander into the gym every now and then and say hello to the players. Harding would storm over, get right in the priest’s face, and seethe like a drill sergeant, “Don’t you ever come in here and interrupt my practice.” In a matter of weeks, the man had completely destroyed my confidence.

How so?

At Dodge City, I led the conference in scoring. I could put the ball in the basket. But when I got to LaSalle, Coach Harding told me in his drill-sergeant way to run the offense, play defense, and serve as the team captain. Period. He said, “I didn’t bring you here to shoot. I’ve got enough All Americans to take the shots.” The only shot he allowed me to take was an uncontested layup. In practice, if I took a wide-open jump shot, he’d blow his whistle and rant. “Didn’t I tell you not to take that shot? Start running.” I’d have to do laps around the gym. I averaged three points per game that year.

And that’s when you became a defensive stopper?

Well, I’d always been a good defensive player. But because I’d lost confidence in my shot, I concentrated more on playing defense. Believe me, I stopped guys. I didn’t slow them down; I stopped them. I didn’t think nobody could score on me – until I ran into a guy named Calvin Murphy. He put 52 on me.

How’d that happen?

|

Murphy played for Niagara, and we played them my junior year. I’d heard that Murphy was a great player, but Coach Harding told me that he was confident that I could handle him man to man – no help, no switches – for 40 minutes. I was all pumped up. I was going to make Murphy’s life miserable. I remember a few days before the game walking back to the dorms with Bernie Williams and Kenny Durrett. They said, “Fatty, we have a lot of respect for your defense. But you can’t play this cat full-court, man-to-man without any help.” I said, “Want to watch me?” I had that much confidence in myself.

I’ll never forget the night of the game. It was at the Palestra, and the house was packed, in part, to see me handcuff the amazing Calvin Murphy. Niagara got the tap, and I stood at the top of the key just waiting for Murphy to bring it on. Let me tell you, Murphy went by me so fast that it’s the only time in my life that I ever got scared on the basketball court. He had put the ball through the rim before I could even turn around. I kid you not. Murphy took all of the shots for Niagara, so I spent the entire game bouncing off of picks. I’ll never forget what happened next as long as I live. Coach Harding came into the locker room afterwards and smirked, “You’re supposed to be the best defensive player in the country. You ain’t shit.”

Nice guy. But LaSalle finished the season 20-8, right?

|

Oh, we had great talent! But we lost to a real good Columbia University team at Cole Fieldhouse in the first round of the NCAA tournament. After the season, Coach Harding pulled me aside and grumped, “Fatty, if you don’t average over 10 points per game next year, you won’t be in the starting lineup.” I said, “I’ll have to get a lot of steals then.” Remember, the only shot I could take was an uncontested layup.” Harding replied, “Well, I think you could average five steals a game.” So, I piped up and said, “If you give me the green light, I’ll score 20 points per game for you.” He just ignored me, and I lost it. I went after him, and the other guys pulled me off. Long story short, Harding kicked me off the team. I still had my scholarship, but I was off the team.

So what happened?

I went down to Kelly Miller playground that summer, and everyone was whispering, “What happened to Fatty? He done lost his game.” That’s when I called Dave Bing. He had a basketball camp up in the Pocono Mountains, and I asked him if I could come up there. In August 1968, I picked up the newspaper one morning and saw a headline in the sports section. “LaSalle’s Harding Fired.” I was pumped up now. I went back to LaSalle that fall, and the new coach was the 35-year-old Tom Gola, the basketball legend. Although we were on probation for something Harding had done, LaSalle went 23-1 that season. We were number two in the country.

A Token Draft Choice, A Little Luck, and a Long Pro Career

Your senior year at LaSalle, were you thinking about the pros?

Oh, I never thought about playing pro ball. I was just worried about getting my degree in sociology. I wanted to return to D. C. and get into social work, coach kids, and help them make it. But I got drafted by the Philadelphia 76ers. It was a token thing. I had played my college ball at LaSalle, and the 76ers took me in the last round of the draft, probably just have enough bodies in training camp before they started making the cuts.

But you almost made the team.

Yeah, I played well. The 76ers had two all pros in the backcourt in Archie Clark and Hal Greer. The backups were Wali Jones and Matt Goukas, both of whom had grown up and played their college ball in Philly. When Coach Jack Ramsey cut me, he looked me in the eye and said, “Fatty, you made this team. But due to circumstances beyond my control, I can’t keep you.” So, I felt good when I walked out of his office. I had proven to myself that I could play at that level.

And that’s when you went to the ABA?

That’s right. One of the Philadelphia sportswriters told Coach Al Bianchi of the ABA Washington Caps about me right away. Bianchi called and asked me to tryout for the Caps. I told him that I’d come as long as he didn’t already have his team picked. Well, the Caps had won the ABA championship the year before in Oakland with Rick Barry. All of their guards were back, and the team’s top two draft choices were guards. But Coach Bianchi promised on the phone to give me a fair shot. So I worked hard in training camp, kept my mouth shut, and was a much better defensive player than any of the other guards. I think Bianchi decided to keep me because he needed somebody on his roster to play some defense.

The Caps played in Uline Arena. What was that like?

The place was always cold, and they had some hard-nosed fans up there in that neighborhood. But hey, I was happy. My contract was for $15,000 that year, with a $2,000 bonus for making the team.

You must have felt good to be back home?

Well, I’ll tell you what happened. I’d played great during the exhibition season, but when the regular season started I was anchored at the end of the bench. Then one game, the starting guards were out injured and a couple of guys got hurt in the first or second quarter. I was the fifth guard, and Bianchi didn’t have any choice but put me in the game. We were down by 17 points, and I got in there and played like a wildman. We closed the gap but ended up losing by two points. The next day, the newspaper ran an article about how I had almost become an ex Cap. Management had planned to cut me right after the game.

So they didn’t cut you?

No. See, when you’re sitting on the bench, they don’t know whether you can play or not. So, it’s easy for them to cut you. Nobody’s going to second-guess the decision. But once you get out there and show what you can do, people start saying you should have been playing from day one. So, I made it hard for them to cut me after that game.

Did your minutes pick up, too?

They did. Everybody was hurt, and I ended up starting alongside Larry Brown. Those are the breaks of the game. Had everyone stayed healthy, I probably would have never played pro ball. Back then, you still had relatively few pro teams, and a lot of ballplayers looking for work. But I was in the right place at the right time. I proved myself, and the Caps became the Virginia Squires the next season.

What was it like playing in the ABA?

Most of the players were extremely proud of the league. It was our league, and we wanted to see it work. We wanted to prove that we were every bit as good as the NBA players. The NBA might have had better big men on the whole, but we had great guards and forwards in the ABA. Julius Erving, George McInnis, Roger Brown, Donnie Freeman, Charlie Scott. Need I say more? One thing about the ABA. If you played poorly or started acting up, you were gone. They’d get somebody else to take your spot. You could never be complacent. You had to stay hungry. So the games were real competitive. But the thing was, even though we’d beat each other up for four quarters, we’d all go out afterwards and party together. We had a really close-knit family.

If you were a close-knit family, how did it feel when players jumped leagues? Was it like losing a family member? Or was it just seen as a business decision?

Both. Whenever the news broke that one of our better players planned to jump to the NBA, we didn’t want to see him go. We knew it would weaken our league, and that hurt everybody. So, the news always was disappointing. But pro basketball is a business, too, and players have to look out for themselves while their legs are young and healthy. The leagues were engaged in a bidding war for talent, and the ABA brought in many players from the NBA. It went both ways.

You played pro with Julius Erving in his rookie year. What did you think when he arrived in training camp as a rookie? He had been primarily a rebounder at UMass.

When I went to Virginia that second year, nobody knew much about the Doctor when he arrived in camp. That changed quickly. He was slamming from the free-throw line, had those big hands, and was doing things with the basketball that I’d never seen in my life. It was incredible. Playing with Doc and Iceman [George Gervin], that was the highlight of my whole career.

But you played with many other great ones.

That’s right. I played with Rick Barry in Washington. In Virginia, I also played with Charlie Scott, one of the best. In Denver, I played with David Thompson, Bobby Jones, and

Ralph Simpson. So, man, it was a beautiful thing.

And don’t forget D.C.’s own Bernie Williams.

That’s right, we hooked up again in the pros. Bernie got drafted by the NBA San Diego Rockets, and I went to the ABA Virginia Squires. The Rockets cut Bernie after two years, so I told our coach Al Bianchi that Bernie could come here and help us. Bianchi joked that Bernie might come in and take my job, and I said, “No, no, we play different styles.” Bernie ended up having a fine pro career.

Reflections on a Wonderful Life

What are you doing these days?

I run a non-profit organization in the Denver area called Taylor-made Playez. We house kids, mentor them, and try to place them with colleges. The bottom line here is other people.

Looking back on your career, what did basketball give you?

Oh man, basketball gave me the opportunity to meet people from all over the world. I got to know people of different races and cultures. It made me more aware. That helped me gain a better understanding of myself. I realized that if you put your mind to something – and work hard – you can succeed in anything.

Nowadays, lots of kids view basketball as a means to a materialistic end, namely, pro riches and its trappings. But it’s so much more than that.

Absolutely. I never thought about playing pro ball as a kid. True, the pro game allowed me to live in nice homes, drive nice cars, and all of that. That’s been great. But it misses the larger truth. You don’t have to turn pro to be blessed by this game. I coach teams here in Denver, and I see kids who want to play for the Lakers or the Knicks. I say just be lucky. Go get yourself a college degree. Don’t set your sights on pro ball. You have a better shot at hitting the lottery than playing pro ball. I say just play ball and enjoy it.

Thanks for sharing your story.

My pleasure.