Talley the Terminator, he gave you Buckets

When Archie Talley was about six years old in the late 1950s, his family lived in an apartment complex that straddled the Northeast D. C. and Maryland border. Not far outside his front door stood a swing set. But the older kids always swiped the swings, so Archie had to invent his own entertainment. He started tossing a little ball at a tomato-sized red spot on one of the swing supports.

When Archie got a little older, he wandered up the block to Seat Pleasant Elementary School, saw a set of monkey bars, and invented a new game. He tried his luck lobbing a cantaloupe-sized rubber ball through the narrow gap between the metal handgrips at the top of the monkey bars.

“You had to loft the ball up high so that it landed right in the middle,” said Talley, whose father and hero Archie, Sr. was the top chef at the prominent Hay-Adams Hotel across from the White House.

“If you didn’t, the ball would bounce right out. I’d be out there all day long shooting at the monkey bars. That’s how I developed my shooting touch. When I was old enough to walk up to [nearby] Watts playground on my own, it was easy for me to shoot at a basketball hoop.”

So much so, Talley earned All-Maryland honors in 1972 as a senior at Central High School in Prince George’s County. But the college coaches weren’t interested in Talley’s rail-thin, six-foot-one physique. Central’s coach Bob O’Brien made a few phone calls on his guard’s behalf but got nowhere. Talley, who couldn’t afford to pay for college, was out of luck - and so, too, were his hoop dreams.

As winter turned to spring, Talley’s only hope was tiny Salem College in the central West Virginia town of the same name. Talley had never heard of the college. But Jerry Keith, a Salem alum and assistant basketball coach at rival Mackin High School, said he planned to drive there in a few days to have his six-foot-nine center Fred Bailey tryout for a scholarship. He asked Talley to tag along. Maybe he could tryout, too.

“When Jerry picked me up on Saturday morning, Fred wasn’t in the car,” Talley remembered of his first visit to meet Salem’s basketball coach Don Christie. “Fred had gotten sick and couldn’t make the trip. Jerry said Coach Christie didn’t know that Fred was sick, but we were going anyway.”

Keith headed north past Frederick, Cumberland, Frostburg, and veered south around Morgantown. About 30 minutes later, a solitary green exit sign announced Salem, a mostly white town of about 2,000 known for its frontier log houses and apple butter festival. Beside him the eighteen-year-old Talley wore a blue, crushed velvet suit and a wide-brimmed hat that gave him the loud look of a big-city hustler. Talley didn’t care. The movie The Godfather was out, and dressing like a gangster was all the rage in Southeast Washington, where he and his family now resided.

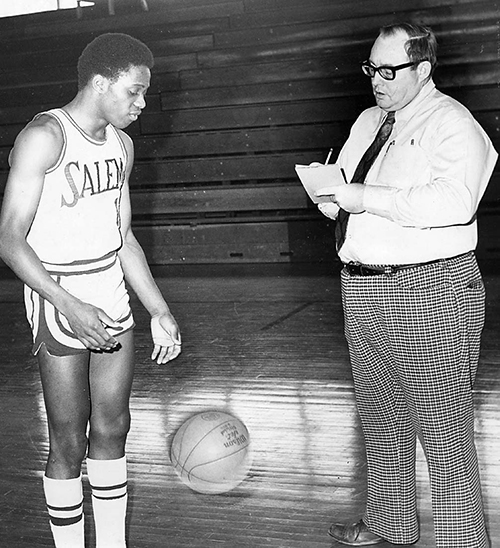

“When we finally got there, Coach Christie expects to see this six-foot-nine King Kong roar out of the car,” said Talley. “All of a sudden, the car door opens, and I jump out. Christie was like, ‘Who’s this little guy? Where’s Fred? Get me Fred.’”

“I kind of laughed to myself when I saw Archie get out of the car,” recalled Christie. “Here he is in Salem, West Virginia, where dressing up is wearing a new pair of blue jeans, and he is in a blue velvet suit and a wide-brimmed hat. He stuck out like a sore thumb.”

Christie kept an open mind and greeted his big city arrivals politely. He invited Talley to change into his gym clothes and take a few shots in the gymnasium for him. After about twenty minutes of shooting, Christie called Talley to the sideline and told him he had a spot on the team. His new coach began rattling off the acronyms for the various financial aid packages, and the overwhelmed Talley cut him off. “Excuse me, but I just have one question,” he said. “Your answer to this question will determine whether I come here. Do I have to pay anything to go to college?”

“You don’t have to pay a penny,” Christie answered.

“I’ll sign,” Talley interjected.

“No, I want you to go home and discuss it with your mother.”

“She’ll sign, too.”

And so the legend of Archie Talley began. Talley was one of those rare individuals with the drive and self discipline of a U. S. Marine. “I’d never seen anything quite like him,” said Christie. “We practiced at the armory, which is about three miles from campus, and Archie would jog back to the college after practice. The other guys would be dying, and Archie didn’t think I had worked him hard enough. He had a heart rate of about thirty five.”

Talley also was a natural showman who played with flair and always made time for kids. “You’ve got to remember, basketball was easy for me,” said Talley. “I thought if something that came as natural to me as basketball can make so many people happy, I should use this gift to give joy to people.”

The person whom he most wanted to please was the man who gave him a chance, Coach Christie. Despite their cultural and generational differences, Talley discovered in Christie a happy-going, color-blind genuineness that he’d never encountered. “He used to call me up in the dorm and ask, ‘Do you want to come over and watch TV?’ said Talley. “He didn’t have an ulterior motive. That’s just the way he was.” During Talley’s freshman year, in one of the great games of the season, Salem upset arch rival Fairmont State, then the nation’s number-one ranked small college team. So big was the victory, Salem’s president closed school the next day.

Talley couldn’t share in the euphoria. As a city kid, raised on the Washington Redskins and Baltimore Bullets, he had never heard of Joe Retton and Fairmont State until a few months earlier. “The joy for me was what it did for Christie, the town of Salem, and the whole college community.” he said. “It was like the best thing that had ever happened to them. Ever. It brought not just joy, but pride. These were people who deserved to be happy, and I could help them feel good about themselves. It was a beautiful feeling.”

As a freshman, Talley averaged 22.6 points per game, a spectacular total for any first year college player. In small-town Salem, a rumor spread that D-I Memphis State wanted Talley. “I went to see Coach Christie one day, and he looked like he’s just seen a ghost,” said Talley, who had not heard the rumor or even spoken to Memphis State. “He kept saying, ‘Archie, I promised your mother that I’d teach you how to drive,’ and ‘Archie, I told your mother that I’d make sure that you got your diploma.’ Here, Coach Christie thinks that he just lost his best player, and all he could think about was his obligation to me. That’s how special Salem was.”

In 1974, his sophomore year, Talley boosted his average to a league-leading 29.4 points per game. The following season, the kid who the college scouts didn’t want was the second-leading scorer in the country with a 34.9 average. Across West Virginia, people were talking about “this kid Talley.” He arrived at games dressed like a Motown star and did things on a basketball court that nobody, not even the pros, could do.

“Archie had certain nuances to his game that were ahead of his time,” said Penny Greene, who played against Talley in high school. “He was the first player that I’ve ever seen dribble the ball from hand to hand behind his back full speed. You know, you see kids today do it, but it’s used to escape defensive pressure laterally. Archie used it as an offensive weapon. He came straight at you with it and put you back on your heels. To this day, I’ve never seen anybody else with the dribbling skills to do that in a real game.”

“To this day, he is the best long-range shooter that I’ve ever seen,” said Chris Wallace, a native Buckhannon, WV and currently the general manager and vice president of basketball operations for the NBA Memphis Grizzlies. “Archie was within range one or two dribbles over halfcourt. Salem once played a preliminary game in West Virginia University Coliseum. The court has an oversized outline of the state marked out at halfcourt. I didn’t see the game, but I people came back and said, ‘My goodness, he was shooting from the Eastern Panhandle.’”

In 1976, Talley returned for his senior year to a team that graduated four starters. When Salem’s point guard went down with an injury, Talley took over. “Archie tried to compensate for the inadequacies at the other positions, and his legend just got bigger and bigger,” said Christie. “Things just got out of control.”

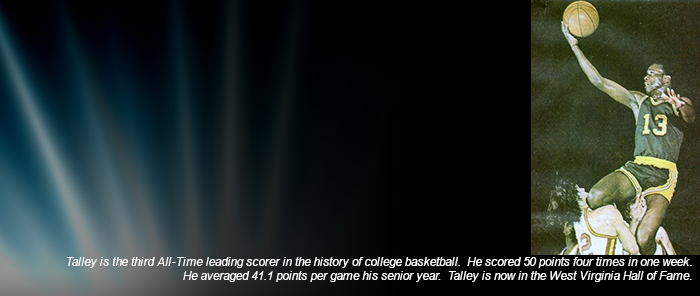

As most college and pro players say, a forty-point game is impressive. Stringing together three forty point nights in a row is a remarkable accomplishment. For Talley, that was small potatoes. He clicked off four fifty-point nights in one week. After a twenty-five point outing to snap the string, Talley finished his career by scoring thirty points or more in twelve straight games, with most of those totals in the forties, fifties, and sixties. Remarkably, with every defense designed specifically to stop him, Talley connected on 49 percent of his shots from the field and still holds the NAIA single-season record for shots attempted and shots made.

Talley played his final game at Salem in the West Virginia Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Tournament (WVIAC) quarterfinals against Fairmont State. Mike Philippi, who starred at WVIAC-member Shepherd College, remembers the moment well. “Near the end of the first half, Archie brought the ball upcourt, and Fairmont’s Davey Moore crouched at halfcourt waiting for him, his hands on the ground,” he said. “Archie started going between his legs about halfway to him, then just started dribbling behind his back the last twenty feet. When he got to Davey, he juked a few times, blew past him, stopped on a dime, and swished a thirty footer. The crowd went nuts, and Archie does that two or three times.”

“Fairmont decides to hold the ball for the last shot of the half,” said Philippi. “The ball gets knocked loose and bounces to Archie on a dead run. There’s maybe five seconds on the clock, and Archie has two Fairmont defenders in front of him. He pulls up near the top of the key, and both defenders lunge at him. Archie rises up to shoot, hangs in midair for a second, then throws the ball between his legs to a teammate who lays it in at the buzzer. The place goes crazy.”

Talley finished the season as the nation’s leading scorer with a 40.8 point-per-game average. He also set an NAIA record 1,347 points scored in a single season, or thirty four points shy of Pete Maravich’s NCAA record. Like Maravich, Talley played without the three-point shot. Had Talley played with the trifecta, he realistically would have averaged more than fifty points per game, earned national recognition, and ended up as a second or third-round NBA pick.

Instead, the New York Knicks selected Talley in the ninth round of the ten-round 1976 NBA draft. Talley hired an agent and waited for the Knicks, like Coach Christie four years earlier, to say they wanted him. The kind words never came.

“I was just a kid,” said Talley. “I didn’t know that the Knicks don’t call unless you are a first-round draft choice. So, I chose the team that showed interest in me and seemed to want me. That team was the Harlem Globetrotters.”

Talley seemed like a natural to whistle “Sweet Georgia Brown” - and that was his downfall. Meadowlark Lemon, the star of the Trotter show, was notorious for eliminating any fresh face that one day might steal his thunder. Talley represented a threat and, after a month of training camp, Lemon let Talley go.

After a season in Venezuela, Talley returned to America and participated in the Knicks rookie training camp. Talley did well and received an invitation from the Knicks’ coach Willis Reed to participate in the upcoming veteran camp. Reed leveled with Talley. The Knicks had eight veterans coming into camp at Talley’s position. He could only keep five, and all eight had guaranteed contracts.

“You could be the best player in camp, and I’d still have to cut you,” Talley remembers Reed saying.

Reed encouraged Talley to tryout with the New Jersey Nets, where his chances to make the team would be better. Talley worked hard in the veteran’s camp, and Nets’ coach Kevin Loughery kept him through eight preseason games. According to Talley, he made the final cut and the team’s unofficial opening-season roster.

Then business struck again. Loughery was summoned the day before the regular season started to meet with the team’s owners. He handed them a sheet of paper with the roster and said he planned cut guard Dave Wohl, who reportedly was entering the third year of a guaranteed five-year contract. If the Nets cut him, the owners would have to pay him approximately $350,000 per year for the remainder of his contract.

The owners asked about Talley’s contract, which would go into effect in a day. He would earn $45,000 the first year and $55,000 the following year. The money wasn’t guaranteed. The math was simple.

“We had just played the Baltimore Bullets in our final preseason game, and Kevin Loughery called me over to the side,” said Talley. “I thought he was going to say don’t be nervous in the opening game. He said, ‘Archie, you’ve done everything that we’ve asked you to do. We want you on the team, we need you on the team, but we can’t keep you. I’m going to have to put you on waivers.’ I was in shock. Thirty years later, I’m still in shock.”

The next day, the New York Post ran an article with the headline, “Nets cut ‘helluva player’ Talley.” Wohl played ten regular-season games and averaged 3.5 points per game for the Nets in 1978. Talley took his act overseas for several years, including a stint in a German B league, where he once scored 113 points in a single game.

“I learned the business end of the NBA,” said Talley, now a successful motivational speaker who is known for shaving while spinning a basketball on a razor. “There’s nothing that you can do about it. I was in the right place with the right coach at the wrong time.”