One-On-One With: Gary Williams, Part 1

Barry Jacobs | Mailbag

March 16, 2010

Maryland’s Gary Williams is among the most successful basketball coaches in ACC history. He’s also a volatile sideline presence who somehow has never received the full measure of appreciation his accomplishments merit.

Only two coaches in the league’s 57 years, North Carolina’s Dean Smith and Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski, have amassed more victories than Williams’ 202 in ACC competition. Now in his 21st season at College Park, he has 441 wins at Maryland, more than anyone in school history, and 648 career victories through March 11, 25th all-time among Division I coaches.

Williams, who turned 65 on March 4, is among seven ACC coaches who won a national championship (in 2002) and among seven who made repeat trips to the Final Four (2001, 2002). His team won an ACC Tournament in 2004, and he led the Terrapins to first-place league finishes in 1995, 2002 and 2010. His Maryland teams have won at least 19 games for 14 consecutive seasons.

The NCAA Tournament trip this month is the 14th for his program, including 11 in a row from 1994-2004.

The ACC Sports Journal, via contributor Barry Jacobs, recently spoke with Williams about his playing days at Maryland as the program broke the color barrier, influences on his coaching, how the game has changed, and some of the more idiosyncratic aspects of his behavior on the bench.

This is one of the longest interviews we’ve ever run. We’ll be running it in segments the rest of this week. This is part one.

ACCSports.com:

How did a Jersey guy wind up at Maryland in the first place?

Williams:

It’s interesting. I lived in South Jersey, which is only, say, 30 miles from the Delaware Memorial Bridge, so you’re into Delaware pretty quick. If you look at the state of New Jersey, besides Princeton — nobody could get into Princeton, so you didn’t worry about that as an alternative — there weren’t many schools. You could go to Rutgers. Back then, Rutgers, it’s still the wrong name, it should be New Jersey State, just like N.C. State. It’s a bad name. I guess Rutgers gave a lot of money, so they got the name.

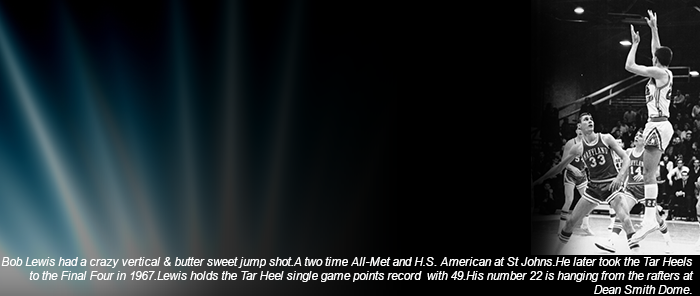

I was a decent player. I visited Clemson, Pittsburgh, Providence and Penn. I would have gone to Penn because my buddy went to Penn. He was a senior when I was a junior in high school. He was a great player, he was All-Ivy League. Three years only. Unfortunately, he played the same three years as (Bill) Bradley (at Princeton), so nobody heard of him.

So I visited Maryland, and it was Eastern Regionals, and Cole Field House was unbelievable back then. I walked in at that street level in Cole. I’d been to the Palestra, but you could fit the Palestra in Cole Field House, and I just said, “Whew! Man! This is where I want to go.” So I picked Maryland. Very good reason.

My high school coach (John R. Smith) wanted me to go there, too. He thought that he’d be closer to me there; it’s only a 21/2-hour car ride to get to Maryland. He was really good. He was a great high school coach, and he took care of me when I was in high school. I still talk to him. He’s a good man.

ACCSports.com:

When you were at Maryland, was the campus immersed in the rise of the civil rights

movement, the anti-war movement?

Williams:

No, there was nothing like that. Come on.

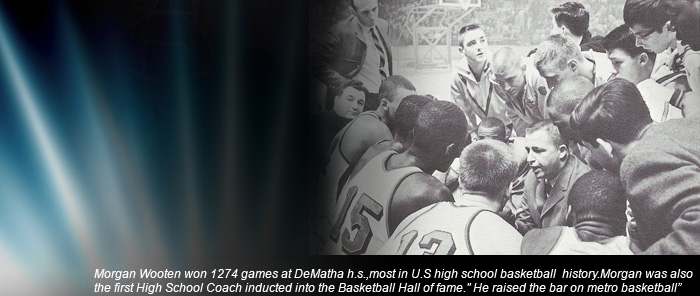

Bud Millikan had started to receive some criticism, even though to this day I’ll put him against anybody in terms of fundamentals. His style of play was wrong for the time, because here comes Vic Bubas (at Duke), with Hubie Brown and Chuck Daly as assistants. (Frank) McGuire’s at South Carolina. The conference was changing. Bud was stuck at Maryland with one part-time assistant (Frank Fellows). That was his staff, and he was supposed to out-recruit those guys.

So he was just in a situation where he wanted to win.. Bud was a very good competitor. He played for Henry Iba, so he was a great competitor. Where we were, I think Maryland always kind of considered ourselves a northern school. We’re right on the edge there. The Mason-Dixon line’s right around there. So, anyway, we’d play Kansas, Kansas State, one year, they’d play three black starters, four black starters. We were around major cities. We were around D.C.., Baltimore, Philly.

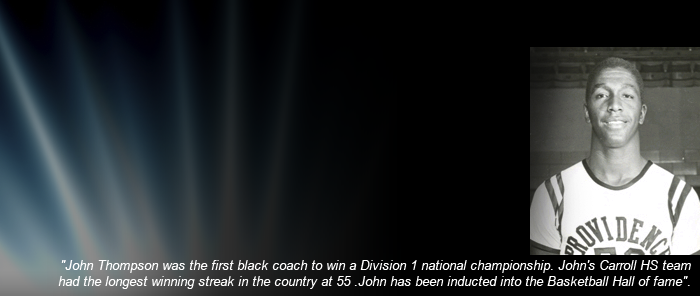

I’m sure there were some people that were glad when he did get fired in ‘67 because of doing that (breaking the ACC color barrier with Billy Jones and Pete Johnson in 1965). I wouldn’t be surprised if they were Maryland alums back then, I’m talking 40 years, guys that just didn’t like the idea that it happened. But if they stepped back, they would say, well, it was going to happen sometime. But they didn’t like that it happened then, (because) it affected their school.

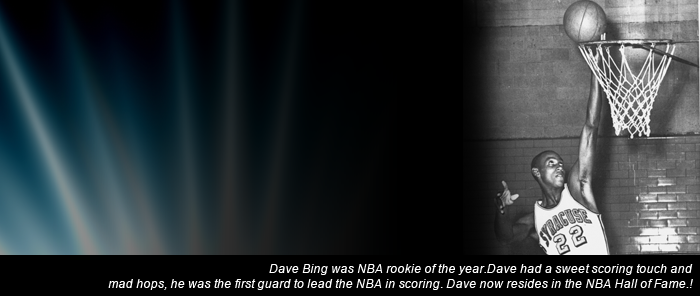

But Billy Jones and Pete Johnson were great guys. Pete was kind of a legend there. A lot of people thought he was going to be the next David Bing growing up. I think he went to Fairmont High right there on the D.C.-Maryland border. He came in, and you could tell Pete had been in a different place than Billy Jones. Billy was pretty sophisticated coming in, where Pete was like, “Wow, there’s no black people here.” The whole thing. There was probably 100 black students on campus at the time.

That was how those guys got there — Millikan wanted to win games. I liked it. He was being honest. If this is the best player that I can recruit, what the hell’s wrong with bringing in a black guy? That was his attitude.

Billy was tremendous. It’s a smaller stage, obviously, and I didn’t know Jackie Robinson, but they all say what a great job Jackie Robinson did. If he was a different way, it might have hurt things for a long time. Billy was the same way. He made it OK for Charlie Scott to go to North Carolina, and he never got credit for it. I never thought Billy got any credit at all for what he did, because there were things said. I could hear things.

One road trip was at Clemson, at South Carolina. Back then, in say ‘66, was Billy’s first year. I would say that there’s a good chance there that, besides people that swept the floors, there had never been a black person, player or fan, in the building. I’m guessing. I think that there’s a good chance that was true. And, so, they didn’t like it, grew up a certain way, didn’t like the idea. Because I think they could see the game … to them, that was the end of basketball, to a lot of people. It was going to change. It wouldn’t be the way they grew up playing basketball.

It was a tough thing. Billy just stayed focused. I don’t ever remember him ever reacting. Not that he didn’t hear things, not that he wasn’t pissed off, but he really did a great job. He was a good guy to hang around with. We had a good time. He was funny. We’d mess around. Every once in a while, we’d make a threatening phone call to his room, in South Carolina or someplace like that. He seemed to get over that.

ACCSports.com:

You’ve said before that you picked up things from watching Bubas, Dean Smith and Earl Monroe.

Williams:

See, Earl Monroe was from Philadelphia. I could get to the Palestra in a car 25 minutes from my house where I grew up. I played a lot in the summertime. By about 10th grade, you started going over to Philly to play some games. Back then it wasn’t the organized summer leagues as much as it was pickup games. You could play, there were never any problems, you could go into black neighborhoods and play. That was never a problem.

I just remember hearing about Earl Monroe. They had this league back there that a lot of pros played in back then, a lot of pros played in the summertime.. It was called the Baker League, and it was like Wilt Chamberlain played there. Bill Bradley would come down from New York and play there. It was just the place to be.

Earl never, never got there on time for the start of the game. He was probably sitting outside in his car. With about two minutes gone in the game, he’d walk in — it was not air-conditioned, it was like 85 degrees — and he had this black cape on. They called him Black Jesus; that was his nickname. He’d walk in, he’d look, go downstairs, get changed and then come up, and then he’d get 60 or something like that. He was the guy.

People that never saw him play or don’t remember him much, he wasn’t a good athlete. He wasn’t the stereotype that a lot of people had. He was probably as smart a player as you could see back then, because he could get guys in the air, he could hesitate. He’d shoot when you weren’t ready for him to shoot. In other words, the great offensive players catch the defensive guy off-balance, where you can’t react, you can’t get off the floor because you’re backing up. That’s what Earl was.

I played one game with him, and I’ll never forget this. He’s in the NBA, and I was probably coaching in high school at the time, so I was playing a little bit in the summer. I’m scared, I’m on the court with Earl Monroe. He threw me the ball. I caught it and threw it right back to him. He comes over during a free throw, and he says, “If I ever throw you the ball, that means you’re open. You’re supposed to shoot it.” That was a great line. That was my moment of fame with Earl Monroe.

Bud Millikan was a traditionalist. He played for Hank Iba, and it was always Mr. Iba. He would not allow you to dribble behind your back. Billy played for a pretty structured guy in high school, too. But Pete Johnson comes in, he had it all. He had all that Earl Monroe (moves). That’s why I loved Pete, because he could do all that stuff. He wasn’t allowed to do it. I really thought Pete should have played in the NBA. He was as good a player as I ever played with at Maryland, talent-wise. He’d walk onto the court, and it was great playing with him, because he never made a mistake.. He was smart as hell on the court.

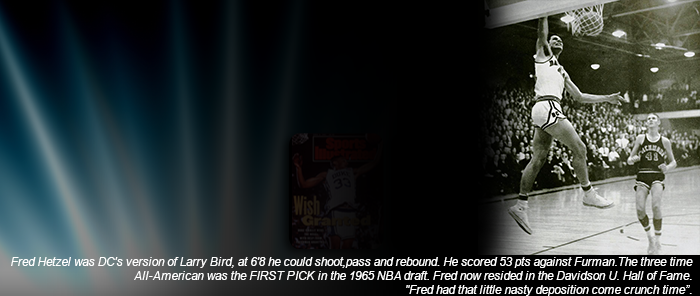

Of course, he was fighting that playground stereotype of Texas Western; there was a connection there between Pete and Texas Western coming in. How could Texas Western ever run as good an offense as Kentucky with Adolph Rupp? That was the attitude of everybody in the stands at that (1966 NCAA championship) game (at Cole Field House). It was the same for Pete coming to Maryland. How could a guy from Fairmont Heights, an all-black school, the whole thing, how could he ever play for Bud Millikan? But he was probably one of Bud’s smartest guards. Bud and him clashed because he didn’t allow Pete to open up his game a little bit.

I tell you what — if we would have ran, Pete would have averaged 20 points a game in the ACC. He was in double figures anyway (13.2-point career average). If you ever check back on Maryland’s guards that played for Millikan, I think Gene Shue was in double figures, but very few guards were ever in double figures that used to play for him, because the ball was supposed to go inside. It was a sound way to play, but the game was changing, the game was changing.