The World According to Garf

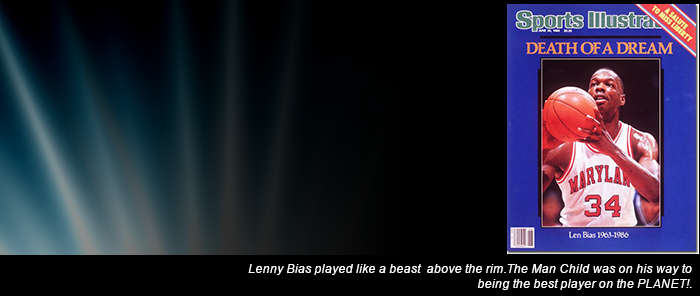

Howie Garfinkel was the godfather of the modern player scouting.

Author: Bob Kuska

What did you do on your summer vacation? For roughly the last 40 years, the D. C. area's top high school basketball players have mumbled the same five words: Went to the Five Star. That would be the Five-Star Basketball Camp, originally based in rural New York and Pennsylvania, and the nation's unquestioned proving grounds for future college and pro stars. As Michael Jordan puts it, the Five Star was "the turning point in my life."

Jordan isn't alone in his sentiments. According to Howie Garfinkel, a cofounder of the camp in 1966 and whose name for decades was synonymous with the Five Star, alumni still pop up in his native New York City when he least expects it to offer an enthusiastic two thumbs up. "Yeah, it's crazy," said 81-year-old Garfinkel, who sold his stake in the camp five years ago. "I'm standing on Fifty-fifth Street waiting for a bus two weeks ago, and one of those big tour buses breezes to a halt near me. The driver strides off the bus to help his riders on their way. Well, he sees me standing there and shouts out, "Five Star! I went to your camp." It happens all of the time. I see cops, rabbis, Indian chiefs, you name it. I can't walk down the street without seeing someone that was at Five Star somewhere."

But Garfinkel, a.k.a. Garf, is more than Five Star. He's the godfather of the modern player scouting service and a man whose imprint on the modern game remains absolutely indelible. Not bad for a kid who, in his own words, "was the eighth man on one of the worst high school basketball teams ever."

Garf recently spoke with D. C. Basketball about his life, his accomplishments, and how attracting Washington-area players to the camp was the key to putting Five-Star on the national map. While this interview digresses a bit from all-things D.C., it offers a unique glimpse into basketball history that can't be found anywhere else. D. C. Basketball delivers. So, let's go back for a moment to the mid 1950s. Elvis Presley topped the charts, college basketball still reeled from the 1951 betting scandals, and Madison Square Garden was still Mecca. That was the 20-something Garf's world. And here is the world according to Garf.

--Garf, your interest in basketball was piqued in the late 1950s when you started coaching an independent team called the New York Nationals. How did that come about?

It all started when I attended an eight-week summer camp. One of my counselors was a man named Mike Kimeberg. He was the original big-time outside ball coach in the New York Metropolitan area.

--What do you mean by "outside ball"?

Outside of high school. Today, they call it AAU ball. But before all of the AAU stuff emerged, independent teams navigated a world in New York that fell under the heading of "outside ball." Kimeberg operated a team called the New York Gems that featured the best outside players in the high school age group. I used to watch the Gems play a lot, and it piqued my interest in basketball. That was step one.

Step two came when the Gems were in a tournament in Long Island City. I went out there to see the tournament, and I heard that the coach of the lousiest team had just quit on the spot. Frank Tempone, who was running the tournament, asked me if I'd be interested in coaching the kids for the remainder of the season. In a moment of stupidity - make that, insanity - I said okay.

--How bad was the lousiest team?

You've seen the old movie Bad News Bears. Well, my guys were the Bad News Bears of outside basketball. Seriously, they could have been the worst team in the history of the game. Let me tell you how bad we were. We once faced a team that only had four players show up for the game. We had all five in tow. We lost by 20 points. True story. You can't make that up.

--But how did you go from coaching famine to coaching feast?

Now that's a good story and gets back to your original question. The regular season ended with one last trip to the woodshed, and that should have been it for my coaching days. But Frank Tempone asked me to enter my team into a post-season tournament for high school junior varsity-and-under players. I said to Frank that I couldn't enter my one-and-done team into the tournament. What was the point? But I told Frank that I'd see if I could assemble a new-and-improved ballclub. Well, new and improved we were. So much so, we won the tournament. I kid you not, sixty-some years later, winning that tournament championship remains the single greatest thrill that I've ever had in basketball. It was just an incredible feeling. To think that we could win it all at this quote unquote big-time tournament. It marked my first taste of success as a coach, and I was hooked.

--And that led to the New York Nationals?

Precisely. I formed an outside team called the New York Nationals. Our sponsor was a tuxedo house called Wexler's Formal Wear. The Nationals started thumping the local competition, and the next thing I knew my team and the New York Gems were archrivals. Let me tell you, things got pretty vicious. Do you know what my career coaching record was with the Nationals? I'll take the silence as a no. My record was 511-151.

--That was quite the dynasty. Why did you hang up the coach's whistle?

I got hooked up with Vic Bubas, a Hall of Famer who was then the assistant coach at North Carolina State for the legendary Everett Case. You see, Vic wanted to recruit the New York area, and the Nationals had some extremely good players at the time, which would have been my fourth or fifth season. Somebody introduced Vic to me, and we started to hang out together. I introduced Vic to my players, and he tried to sell them on NC State. After a while, I turned my focus to scouting for Vic, and I just couldn't keep coaching. By the way, Vic Bubas is the best recruiter that I've ever seen - well, up until John Calipari arrived on the scene. But Vic was fearless, knew every trick in the book, and could charm you off of your feet. On top of that, he was very knowledgeable of the game and always went after the right players. It was a potent combination.

--I know the University of North Carolina was already recruiting in New York by the 1950s. The competition must have been stiff.

Absolutely. For example, my archrival Mike Kimeberg of the Gems was plugged into a guy named Harry Gotkin. He was the recruiter for Frank McGuire of the University of North Carolina. That meant Gotkin had first dibs on sending the best of the Gems to play for the McGuire in Chapel Hill.

--What was Gotkin like?

I thought he was a mean old bastard, may his soul rest in peace. No, he wasn't a very nice fellow to me. It was tough, tough sledding there for a while. Of course, North Carolina got all of the players out of New York. All Frank McGuire had to do was raise his hand, and everyone from New York went running to Chapel Hill. But I was trying hard for NC State. I got very close with Everett Case, Vic Bubas, Lee Carroll, and all of the people down in Raleigh.

--Were Case and Bubas pressuring you to sign players?

Not at all. I wanted badly to get the players for them. I went from gym to gym, playground to playground, recruiting like everybody does today. You like a player and say he ought to go to State, it's a great school, great tradition, great team, great coaches, take a visit, bah, bah, bah. I worked on [now Hall of Fame coach] Larry Brown, who played for me. He wouldn't go. I tried a kid named George Parissi, who also played for me. Same story. I kept losing. Finally, I got three players for NC State - Anton Muehlbauer, Stan Niewierowski, and John Punger. What a disaster! Muehlbauer and Niewierowski were involved in the 1961 fixing scandal for shaving points. Case actually was tipped by their erratic play, contacted the authorities, and turned them in.

--Did you stop recruiting for NC State?

Pretty much. Although State wasn't on probation, Case couldn't recruit anyone for a year or two. So my services weren't needed. I'll tell you, I was sick over the NC State violation. I had just signed a kid for them named Tal Brody from Trenton Catholic High School. Brody was a first-team All American high school player, and I recruited him hard. Everything was set. Brody signed with State the night of his high school graduation. It was beautiful. He was my first true blue-chip recruit. Three days later, the scandal broke at NC State, and that was the end of that. Brody moved on to Illinois. I went from one of the happiest days in my life to one of the worst. You can't believe how crushed I was. I spent two years on him and boom.

--But your stint as a recruiter had a happy ending. It evolved into not only one of the nation's first college scouting services but the bellwether for all that was to come in the modern game. And it started innocently enough with a basketball magazine.

That's right. In 1964, I did the magazine with Murray Rokitch from the New York Journal American. It was called High School Basketball Illustrated. The magazine was 64 pages and had a nice, big-time color cover. I remember driving to a game with Paul Brandenberg, then another NC State assistant coach, and he's got my magazine. I looked at it, and Paul had about 50 names circled with a red pen. I said, "What's that all about?" He said, "Don't you know? This is the best recruiting tool that I've seen. You should do a service." I said, "What's a service?" So Paul pulled out a sheet and showed it to me. It was from a man down in Florida who did a service. Paul told me what it was, how to do it, and said I should start a service for New York players. That was the impetus for the HSBI Report, which started, I believe, in 1965.

--When you look back on your life and its impact on basketball, do you ever wonder, "Why me?" Your father was in the textile business. Were silk and polyester supposed to occupy your life?

Yeah, I suppose I would have inherited the business had my father not sold it. He went out of business and got into entertainment. He became a ticket broker.

--But as a kid, basketball was never destined to be your life's work.

You're absolutely right. I was a baseball player - and not a bad one at that. I was much better at baseball than I was at basketball. At Barnard High School, I was the eighth man on one of the worst teams ever. Based on my service, I'd say that I would have been a 1. Hell, I might not have even made my service. I doubt that I was good enough to be in my service.

--You didn't have a model to follow for the service, right?

No, not really. I just made it up, and things worked out pretty good for 20-plus years. I came up with the five-star system. It went like this: Small college was one star, top small college was two stars, low-major was a three, mid-major was a four, and big-time was a five. We also had a five-plus, which was a super. We had a five-minus, and that was big-time potential. And on and on and on. So, that's how that started.

--But how did you come up with the star system itself?

I stole it from Kate Cameron of the New York Daily News. She was a movie reviewer, and she starred the movies from four stars to one. I just added a star. I don't know if you're aware of this, but the scouting service also popularized the terms big forward, power forward, point guard. See, in those days, there were guards, forwards, and centers. When the service came in, I had to differentiate. I knew that Lou Rossini, head coach of New York University, used the terms small and power forwards, first guard and second guard. I changed things around a little bit. It became lead guard and shooting guard, small forward and power forward. It wasn't exactly rocket science, but those terms came from the service in 1965. Then, of course, the next year brought the Five Star camp.

--How did the camp come about?

Five Star tipped off in August 1965 at Camp Orinsekwa in Niverville, New York. But it was originally called the Roy Rubin Basketball School. Why? The camp was a three-way partnership involving me, Roy Rubin, and Will Klein, who was Roy's assistant at Columbus High School. But let me tell you, there would have been no Roy Rubin Basketball School - and thus Five Star - without a little-known high school basketball coach in New Jersey named Hubie Brown. Yes, that Hubie Brown.

--How so?

Hubie was coaching Fair Lawn High School in a New Jersey township of the same name. I went there one day to attend a basketball tournament and do a little recruiting for my team. Remember Paul Brandenburg, the NC State assistant? Well, Paul told me to try and look up this coach named Hubie Brown. Paul thought Hubie might be interested in working the camp. So at halftime, the school wanted to keep the kids off the court. Three or four adults, one of which was Hubie, stood there like security guards holding a rope around the periphery of the court. I'll never forget it. I walked up to Hubie while he was holding the rope and told him who I was and dropped Paul's name. Hubie told me to see him after the game. So I did. I told him the concept behind the camp. He said that he loved the work and wanted to do it. So I handed him a stack of brochures. I'd say that was in early June. Well a few weeks before the camp starts in late August, I only had 30 kids enrolled. It looked like the camp was dead. Then, one day I get a big manila envelope in the mail. I open it up, and inside are 25 applications from Hubie's people. He had gone around all summer recruiting kids. I had no idea. So, with that manila envelope, we doubled our enrollment overnight. The Roy Rubin Basketball School was a go.

--But not for long. Rubin got out after the first year. Why?

Roy and I weren't getting along real well. But probably the bigger issue was, after paying for the campsite, the profits were pretty underwhelming. Each of us walked away with $340 after months of pounding the pavement. So Rubin said, "I'm outta this." He didn't need the camp anyway. He became the head coach of LIU. Klein stayed. But with Rubin out of the picture, we needed a new place and a new name.

--Well, how did you come up with the name?

A very good friend of mine named Shelly Meier. He owned the Croyton flower shop over on 85th Street and Madison Avenue. Shelly was a basketball buff, and I told him one day, "I need a name for my camp." He thought for a minute and said, "I've got it! There should be five stars on every team. Call it the Five Star Camp." I said, "Terrific." I went in to my partner, Will Klein, and the rest is history.

--How about the new place?

Will Klein found all of the sites. We moved out of Camp Orinsekwa after one year and relocated to a summer camp in Rosemont, Pennsylvania for 10 years. Ten years later, we switched over to the place in Holmsdale, Pennsylvania. During this time, everything just doubled. Seventy kids the first year, 140 campers the next year, 210 the third year. It just kept growing. So I suppose that we were doing it right. We were a teaching camp, and coaches wanted their kids to learn how to play.

--Did you actively recruit your campers?

Oh sure, absolutely. We sent out brochures, of course, and recruiting. The name of the game is recruiting. It was then and still is today. We went after the best players in New York City and New Jersey. Then we branched out to Washington, D.C.

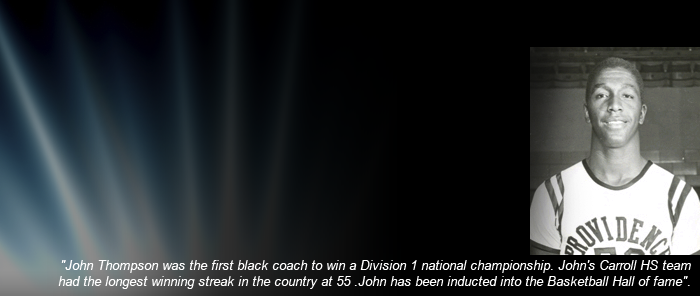

--Tell me how you got into Washington.

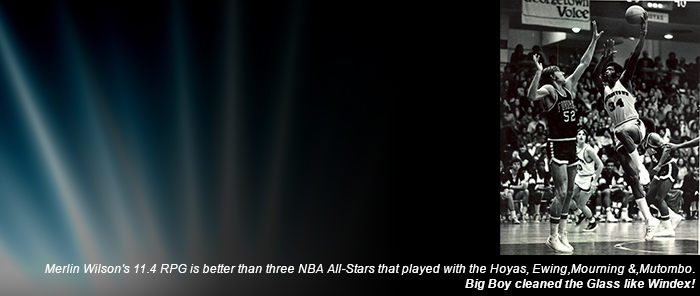

Well, Washington was big. I was looking to branch out, but we didn't. We continued to get our campers from New York and New Jersey, with a few from Philadelphia, too. Then I met John Thompson. I don't remember exactly how we met. But John Thompson was very, very big in the camp's evolution. I recruited him and tried to get him to work the camp. He couldn't. John had two great high school players, Donald Washington and Merlin Wilson. It was probably our third our fourth year. I had an opportunity to get them to come to the camp. So, I recruited them for six months, and finally they came 100 percent through John Thompson. I always did it the right way. I went through the high school coach. Today, everyone goes through the AAU coach. But John Thompson was good enough to send those two players, and that was the beginning of the growth.

I owe the growth of Five Star to two people: John Thompson and Mike Fratello. Mike Fratello got me Moses Malone, and John Thompson started the Washington surge to Five Star, which then included Baltimore. It went from Washington to Baltimore. And then from Baltimore to the whole area. Without Thompson and Fratello, I don't know if the camp would have ever made it. It certainly wouldn't have made it to where it was when I left five years ago.

--So you got the D. C. and Baltimore kids, and the camp just took off?

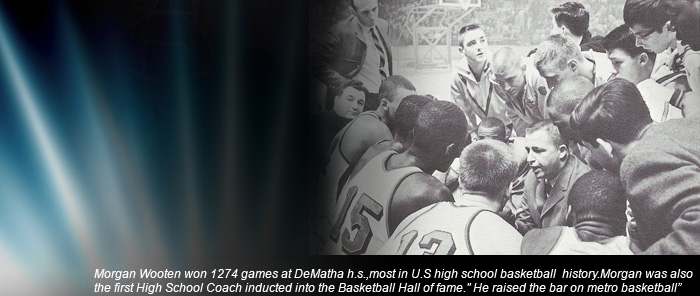

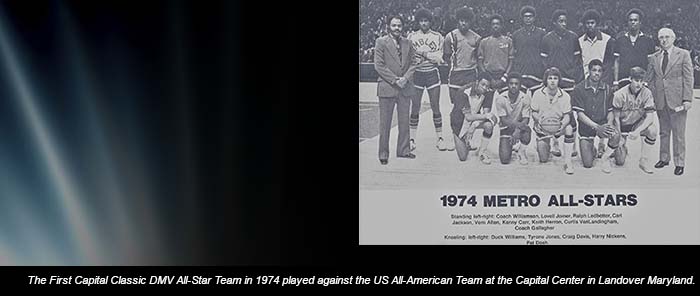

Yes. Everything snowballed. Morgan Wooten sent us players. Joe Gallagher sent us players. Frank Williams did the same. Oh, and Herman Cannon was very big. He sent us a lot of guys. In Baltimore, Bob Wade from Dunbar helped us greatly by sending us all of his outstanding players. He had some fabulous ones. Paul Baker was another key coach. He was outstanding and sent us a lot of kids. I have a great Bob Wade story, if you're interested.

--Go ahead.

Well, Bob is working the camp. We have the players try out first, and then the coaches go into a room and prepare to hold a draft. The first thing we did was pick a number from one through 12 to decide the draft order. The idea being, the coach who gets the number one lands the top pick in the draft. We started the draft with the big men. Well, Wade gets number 12, which means he gets the 12th best big guy in the camp but gets to select the first lead guard. They call it point guard today, but it was the lead guard then. So, Wade picks little Mugsy Bogues. I go berserk. Now I never interfered in the draft. If a coach asked me my opinion, I gave him my two cents but that was it. This time I yelled out, "Stop the draft. Bob, you can't do that." Bogues played at Dunbar for him, and coaches weren't supposed to draft their own players. I told him there were much better players at the camp than Bogues . . . you're ruining the draft . . . the whole week stinks now because your team will get murdered with a five-foot-three lead guard teamed with the camp's worst of the big men. . . just take somebody else. Bob refused. So, I said, "Okay, just wait, you'll see." We went on with camp, and guess what happened? Wade wins the championship, and Mugsy Bogues wins the MVP for the week. He was the best damn little player, and I nicknamed him "The Eighth Wonder of the Modern World." Tyronne Mugsy Bogues. It just shows you. I wasn't always right - just 95 percent [laughing].

--You saw a lot of players from different cities. What was the hallmark of a typical D.C. player compared to, say, a kid from New York?

There was no difference. In my opinion, they were the same. D. C. players were outstanding, in large part because of their coaching. Look at the coaches that came out of the area. I just named some of the big names a minute ago. God almighty, these are exceptional coaches. New York had the same thing. Kids were coached. They were taught.

--Were you overseeing Five Star full time. Or did you have a day job?

I had other jobs. I did everything that you could think of. Let's see. I worked for Bernard Goldfein, which was a woolen mill up in New England. Goldfein & Meadner, it was called. My father got me the job. I picked up a coat one day at Macy's. It was a beautiful Vicuna coat, and that was the coat that somebody in the Eisenhower administration gave somebody. It was a big scandal in 1958. I later worked for Fugazi Travel. I was a terrible travel agent because I'd never travelled. I was telling people where to go, and I didn't travel anywhere. But I had some big customers. I also worked for an assembly line that made shoulder pads for suits.

--And on the side, you did the basketball stuff?

Yeah, I did it on the side. My main three jobs were making the shoulder pads, Goldfein & Meadner, and Fugazi Travel. Then the camp came along, and I still worked.

--So you were a busy man?

Very. I mean, I could go on for another hour about the camp. It's incredible, all of the stories. We had all of the great Washington players. If you name me some names, I'll tell you if they came.

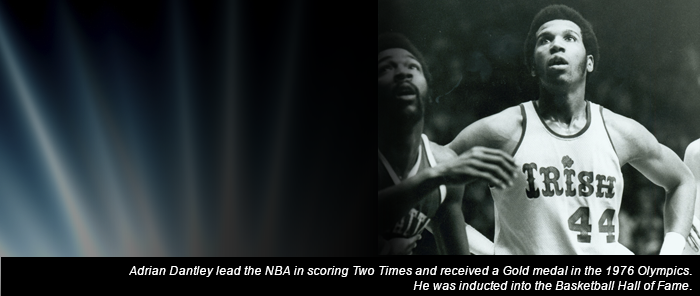

--Adrian Dantley?

Well, you just asked about the one that never came. What are the odds? But I am responsible for him going to Notre Dame, believe it or not.

--How so?

I recruited Dantley for the camp. Morgan Wooten was great, and he sent us a lot of players. We had all of the great DeMatha players - except Dantley. But I was recruiting him, and Morgan and I became friendly. He asked me one day where I thought Dantley should go to college? Well, I told him Notre Dame with Digger Phelps.

--Why Notre Dame?

The Golden Dome, and it was a great school. I knew Digger, and I just thought that it was a natural. Why not? Notre Dame is one of the best. Of the ones that Morgan asked me about, I thought Notre Dame was the best choice. I turned out to be correct.

--Why didn't Dantley come to the camp?

I don't know. We didn't have a lot of weeks back then. Maybe the camp didn't fit his schedule, but I really don't know.

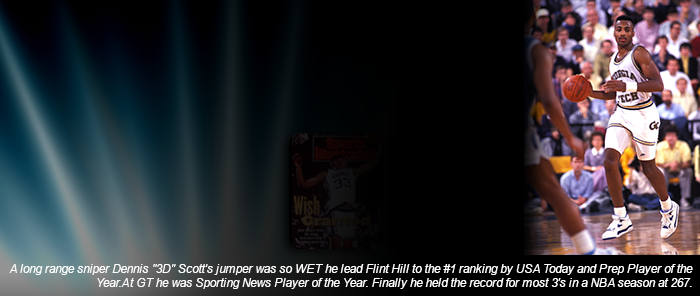

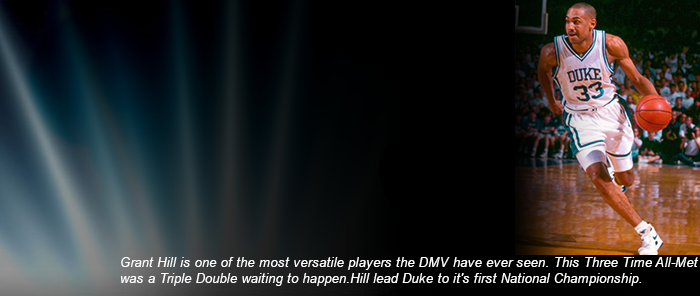

--What about Grant Hill?

Absolutely. By the way, he's finally getting credit now - and it only took 20-something years - for making that famous pass to Christian Laetner at Duke in the NCAA tournament. You've seen the commercial. It's called The Perfect Pass, and it shows Grant Hill throwing the pass. He's finally getting credit for the greatest pass ever thrown in the history of college basketball.

--What kind of a player was Grant Hill?

Phenomenal. He was a tremendous player, tremendous kid. There was a publication called Hoop Scoop. The guy who did the service showed me his list of the top players before we started camp that year. Grant Hill was nowhere on that list. I told him, "Grant Hill has got to be in the top 10." He said, "What?" I said, "That's right, put him in the top 10, or you'll be sorry." By the end of the week, Hoop Scoop had Grant Hill in the top 10. No, he was phenomenal.

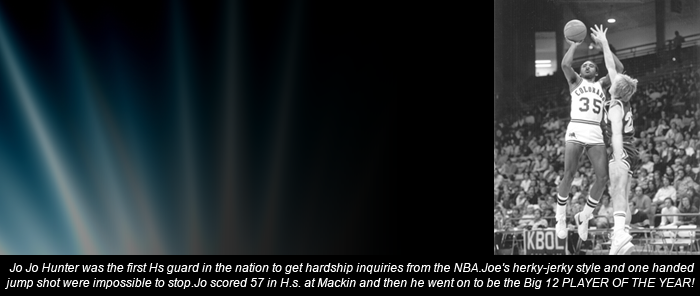

--What about Jo Jo Hunter?

Yep, Jo Jo Hunter was a tremendous player at camp.

--Did Jo Jo have pro talent?

Yep. Jo Jo Hunter was a Five Star immortal. He was just a great player.

--What does "immortal" mean?

Great name, great player at the camp. There have been a lot of them. I can't tell you how many, but he was certainly one of the best that we had.

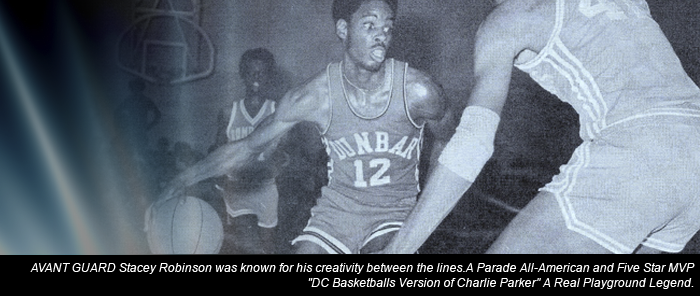

--What about Stacey Robinson?

You know we still talk a lot. He calls me once a week. Stacey was an excellent player, you know, a real slasher to the basket. He could get out on the break, handle the ball.

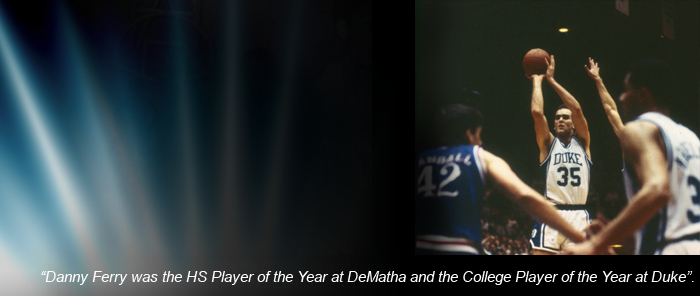

--Danny Ferry?

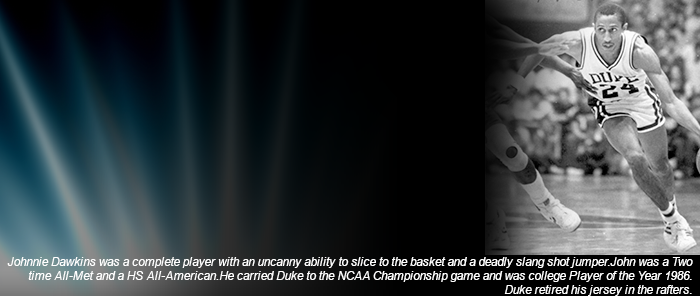

Oh, I've got a great Ferry story. Danny's first year at Five Star was as a rising sophomore at Robert Morris College in Pittsburgh. Call it old fashioned, but we didn't want our sophomores playing at the highest level. We said that they had to earn their way to play in our NBA at Five Star. So, these rising sophomores would come and play in what we called the NIT. Well, they destroyed the NIT. I mean it was unfair. So, we got the idea of segregating the best rising sophomores into one league. We called it the Development League and invited the best rising sophs in the country to join us.

We also took some of our best young coaches and put them in with these kids. One of these young coaches was someone called John Calipari. Yes, that John Calipari. John won two Development League

championships in a row. But he had a thing. Here's what he would do. Whoever his star player was, the second that he did anything wrong in the first game - turned the ball over, didn't get back on defense, you know what I mean - Calipari called time out and buried the kid in front of his teammates. He went nose to nose with him. That was Calipari's trick to get everyone's attention on the team. He was sending a message. Calipari did this in his first two years in the Development League, and he already had his eyes fixed on Danny Ferry, the best player on his team in his third season.

Well guess who is sitting in the stands to watch that first game? Bob Ferry, an NBA general manager and Danny's father. Well, the court is fenced in, and I'm standing there on one side with a few people. Bob Ferry is sitting on the other side. On the game's very first play, Danny Ferry dribbles down the court and misses an open man for a pass. If I remember correctly, Danny shoots, misses, and the opposing team scores on a fastbreak. Calipari signals for a time out. I nudged the guy next to me and said, "Oh God, here we go." Well, for the entire minute of the time out, Calipari has his nose in Danny Ferry's face. Now, he didn't curse. But Calipari is wiping out young Danny like you cannot believe. I glanced across the court, and Bob Ferry is over there observing it all. I remember thinking, "I'm ruined. My camp is over. It's the end." I'm thinking Bob Ferry will tell Morgan Wooten what happened, and I'll never get another DeMatha player. The word will spread, and I'll never get another Washington player. I'm serious. This was my thought process. I'm thinking I just lost Washington. And Baltimore. It's over. My life is over. So I walked over to Bob Ferry to apologize. I stuck out my hand and said, "Bob, what you just saw, you've got to understand that this is a young coach, and he . . . he . . . he does these things." I'm stammering and trying to make things better. Bob Ferry barked back, "What's that coach's name?" Now, I know that I'm really dead. I said, mispronouncing his name, "Kalipury. I think his name is John Kalipury." Ferry said, "No, no, no, you don't understand. I love that guy. It's about time somebody did that to my kid!" That's what he said, word for word. He said, "Kalipury is going to be a great coach someday."

--What about James Brown?

James was very good. He won a rebounding award at the camp, if my memory serves me well. He came to Five Star a couple of times. Do you know the name Anthony Jones?

--Let's see, Jones played at Dunbar. After that, it was a stint at Georgetown, then UNLV, then the NBA.

Right. Jones was a terrific Washington-area player. He won the outstanding player award at the camp in 1980. Jones was a six-foot-five forward who could do it all. His week at Five Star really sticks out for me.

--What about Hawkeye Whitney?

Great player. Hawkeye Whitney and Mike O'Koren (Jersey City, NJ) put on one of the great Five Star weeks of all time. The two went head to head. They played two games against each other and then topped things off with a third and final round in the all-star game at the end of camp. In fact, Hawkeye Whitney might have been the only player that got the best of Mike O'Koren. Theirs was one of the best duels in camp history, you know, just the pure competition between the two of them. Mike O'Koren was just a phenomenal player and one of the all-time best at the Five Star. He'd be in the top 10.

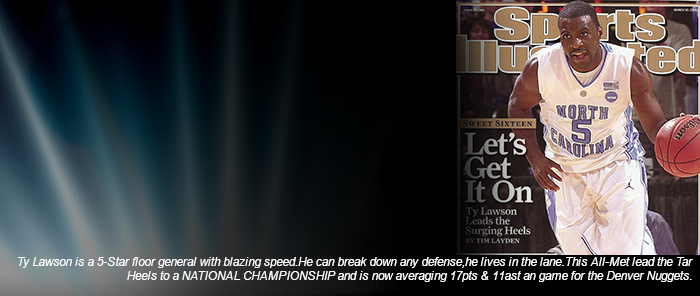

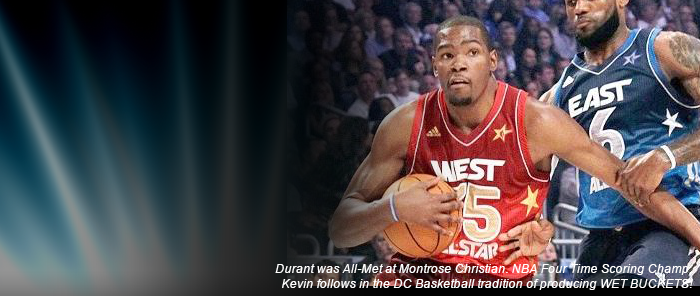

--What about Kevin Durant?

Absolutely. He won an outstanding player award. Kevin will end up being a top 10 NBA player of all time. To think he's still only 24 years old. It's incredible.

--When you watch today's game, what do you think when you see these players play?

Well, today's game is not the same five-man weave that it was when I started the camp. It's just different, that's a good way to put it. But you can't deny the talent. The talent is phenomenal. Just look at Lebron James. I have a great Lebron James story. This told me exactly what he was going to be, and it turns out exactly what he is.

Lebron came to camp as a rising sophomore. I see his first game in the Development League, and he is so much better than anybody else that it's a joke. He's just toying with these kids. I said, "Oh no, this isn't fair." In the meantime, one of the kids in the NBA breaks his leg. I need a player. Bingo. I called Lebron over, told him about the injury, and informed him that I was moving him up to the NBA. I said, "You're too good for the Development League." Lebron answered, "I don't want to go." I almost fainted. I mean, these kids in camp can't wait to get to the NBA. A lot of them, to tell you the truth, you recruit them for the Development League, and they complain. They want to play in the NBA with the best players. Not Lebron. He said, "I really like my team and coach in the Development League. Don't move me." I said, "Okay, tell you what. Do you want to do both? It means you'd have to play four games per day, two in the Development League and two in the NBA." Lebron said he's fine with that. So we move him into the NBA. It was a five-day camp, so he ends up playing 16 games that week in both leagues. He makes both all-star games. But when he told me that "I like my team and coach," I knew what kind of character he has. That's what his detractors miss. Lebron James is the total package.

--Did you have Michael Beasley there?

The Beazer. He played very hard in camp and was a superstar. He won a lot of stuff at the camp. In fact, Beasley might have been an all-time Top Tenner. You know, it's hard. There have been so many great players who have passed through Five Star. The Top Ten ends up crammed up with about 50 names [laughing]. I mean how do you differentiate greatness? I can tell you, though, the names of the top two players of all time at the Five Star.

--Who's that?

Moses Malone is number one. He's the greatest player in Five Star history. Number two was Lloyd Daniels. After those two, it could be anybody.

--So those two were head and neck above the rest?

Well, Moses was. Lloyd Daniels was less so, but let me tell you he was phenomenal. He was like Magic Johnson. Lloyd was the best passer that I've ever seen. You couldn't be a better passer than him.

--But Daniels game didn't translate in the NBA.

Well, Lloyd had run into some personal problems by then. He went south - deep south. But Lloyd is okay now. He's doing a lot of teaching. In fact, many of our former players are running their own camps and basketball schools. Guys like Ed Schilling of Indianapolis. He runs his own school for high school, college, and pro players. It's called Champions Academy. Ed is one of the best teachers of the game in America right now. So, the kids today are still learning the basics, even though they don't attend summer camps like they used to.

--What are you doing these days?

Languishing. I languish [chuckling].

--Is life treating you well?

Well, you know, I'm alive. I wake up each morning and say, "You got another day." I've got a few health problems, and I don't have a job. So, I still do a clinic. It's called The Clinic to End All Clinics. I hold it up at Iona College, and I'm about to do my sixth one. This clinic might be the best that I've ever had. I have Brad Dunphy from Temple. Geno Auriemma, the winningest coach in history. Mike Fratello, who has 600 NBA wins. John Beulein, who is one of the top three current college coaches in America and a phenomenal clinician. And, of course, Bob Knight. Make that, Robert Montgomery Knight. That's my clinic. So, if I don't get 100 people, I'm retiring. I mean, that's a GREAT clinic.

--But if you look at your life, you were truly born under a lucky star. Your timing was right and, lots of hard work later, everything aligned perfectly.

Well, luck is very important. Luck, timing, maybe talent is needed, too. I don't know. Here's what I could do. I'm a very good judge of talent, both players and coaches. Maybe that's because of my family background in show biz. But that's my only talent. And it's worked out. I've picked out some pretty good people over the years. As I told my partner Willie Klein one day, "Put on my epitaph: Every kid got his money's worth." They paid a lot of money, and we always tried to do things the right way. We gave them great teaching.

It's been amazing. When I sold my half of the camp five years ago to my partner, I believe we had something like 320 campers who had played at least one game in the NBA over the 42 years that I was involved. A bigger number than that was we counted up one day 288 college and/or pro coaches came out of the program. Thirty-two of them were NBA coaches. So, it's been quite a run.

--Thanks for taking the time to talk.

My pleasure.